In honor of

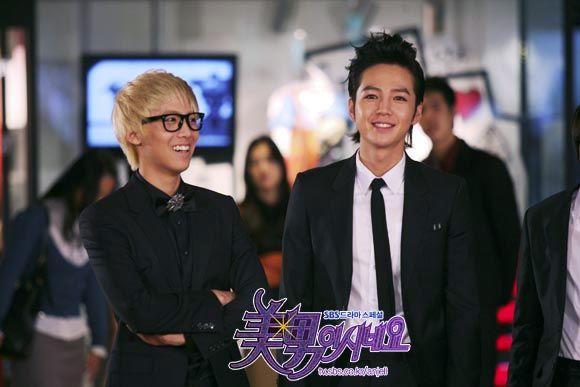

My Girlfriend is a Gumiho premiering

this week, we thought it would be a good time to define what a gumiho

is, and discuss this mythical creature’s cultural implications on

gender, film, and tv. This isn’t a comprehensive definition, by any

means, because there are endless number of myths, folktales, films, and

dramas that feature gumihos in them. But I’ll cover the basics and

discuss what’s interesting about this figure from a cultural point of

view.

A

gumiho [구미호] is a nine-tailed fox, a legendary

creature with origins in ancient Chinese myths dating back centuries.

There are versions of the figure in Chinese and Japanese folklore,

although each differs slightly. The Chinese

huli jing and the Japanese

kitsune

have more ambiguous moral compasses, in that they can be both good and

bad, and are not necessarily out to get everyone. The Korean gumiho, on

the other hand, is almost always a malignant figure, a carnivore who

feasts on human flesh.

According to legend, a fox that lives a thousand years turns into a

gumiho, a shape-shifter who can appear in the guise of a woman. A gumiho

is evil by nature, and feeds on either human hearts or livers

(different legends specify one or the other) in order to survive. The

Chinese

huli jing is said to be made up of feminine energy (yin) and needs to consume male energy (yang) to survive. The Japanese

kitsune can be either male or female, and can choose to be quite benevolent.

The Korean gumiho is traditionally female. Some can hide their gumiho

features, while other myths indicate that they can’t fully transform

(ie. a fox-like face or set of ears, or the tell-tale nine tails).

Either way there is usually at least one physical trait that will prove

their true gumiho form, or a magical way to force them to reveal this

form.

Much like werewolves or vampires in Western lore, there are always

variations on the myth depending on the liberties that each story takes

with the legend. Some tales say that if a gumiho abstains from killing

and eating humans for a thousand days, it can become human. Others, like

the drama

Gumiho: Tale of the Fox’s Child, say that a gumiho

can become human if the man who sees her true nature keeps it a secret

for ten years. Regardless of each story’s own rules, a few things are

always consistent: a gumiho is always a fox, a woman, a shape-shifter,

and a carnivore.

Now on to the cultural meanings. A fox is a common figure in many

different cultures that represents a trickster or a smart but wicked

creature that steals or outwits others into getting what it wants.

Anyone who grew up on Aesop’s Fables knows the classic iteration of the

fox figure in folklore. And it’s not hard to see how the fox got such a

bad rap. The animal is a nocturnal hunter and a thief by nature, and is

known the world over for its cunning mind.

In Korea, the fox has a second cultural implication—that of sexual cunning. The word for fox,

yeo-woo

[여우] is actually what Koreans call a woman who is, for lack of a better

translation, a vixen, a siren, or a sly man-eater. There is a similar

English equivalent in the phrase “you sly fox,” although in Korean it’s

gender-specific (only women get called yeo-woo), and has a much more

predatory “there-you-go-using-your-feminine-wiles-to-trick-me” kind of

meaning behind it. Women who use any sort of feminine charm in an overt

way, or women who are overtly sexualized (as in, asserting and

brandishing their sexuality in a bold way), get called “yeo-woo.”

Interestingly, the word for “actress” [여배우] is the same in its shortened

form: [여우].

It is not by mistake that gumihos are only beautiful women. They are a

folkloric way to warn men of the pitfalls of letting a woman trick you

or seduce you into folly. For an example, see this

translation

of a classic gumiho tale. In many stories the hero of the tale (always a

man) has to “endure” the seduction and unclothe the gumiho, thereby

revealing her true form. Thus a woman’s true nature, her hidden

sexuality = demon.

WTF, Korean folktales?

The concept of female sexuality as dangerous is nothing new to

folklore, for sure. But it’s not a stretch to say that both the gumiho

figure and the use of “yeo-woo” are quite prevalent in modern culture

and its fiction. Most people may gloss over the fact that the gumiho

myth is a story designed to uphold patriarchy. But that’s what makes

such a legend so cunning in its own right.

In film and tv, the gumiho can be both a horrific figure and a

straight-up demon, or a comically laughable one, depending on the genre.

And throughout the ages the gumiho legend has changed, as in

Gumiho: Tale of the Fox’s Child

‘s take on the tortured gumiho with a kind soul who longs to be human

and spares men’s lives. She is a reluctant demon who chooses to walk the

fine line of morality in order to hold onto her human traits. This

interpretation is much closer to the vampire-with-a-soul mythology, as

one being battles the demon within.

But one interesting thing to note in that drama is that the child,

once she comes of age, transforms into a gumiho herself and struggles

with that overpowering demonic force. One can’t help but draw parallels

to a young girl’s own coming of age and sexual development, and how this

myth only serves to further demonize a woman’s sexuality as something

uncontrollable and evil that befalls even the most innocent of young

girls. In this, and other more overtly sexualized depictions, the gumiho

serves to downgrade female sexuality as demonic and directly

carnivorous of men.

All this isn’t to say that female writers couldn’t take ownership of

such a legend and reclaim it. I think that’s the only way to take it out

of this territory and blast all these old versions away with something

empowered. Do I think that’s what the Hong sisters’ goal is? Not

outright. And I’m definitely not going to be watching that rom-com for

its stellar commentary on gender politics. What I

will be doing

is looking forward to the reversal, the woman-on-top dynamic of the

beta male dating a powerful gumiho, and crossing my fingers for a step

in the right direction.

Credit;

dramabeans

Reduced: 93% of original size [ 550 x 319 ] - Click to view full image

Reduced: 93% of original size [ 550 x 319 ] - Click to view full image